Nosocomial and hospital-associated infections in veterinary medicine (NI/HAI)

Fact sheet

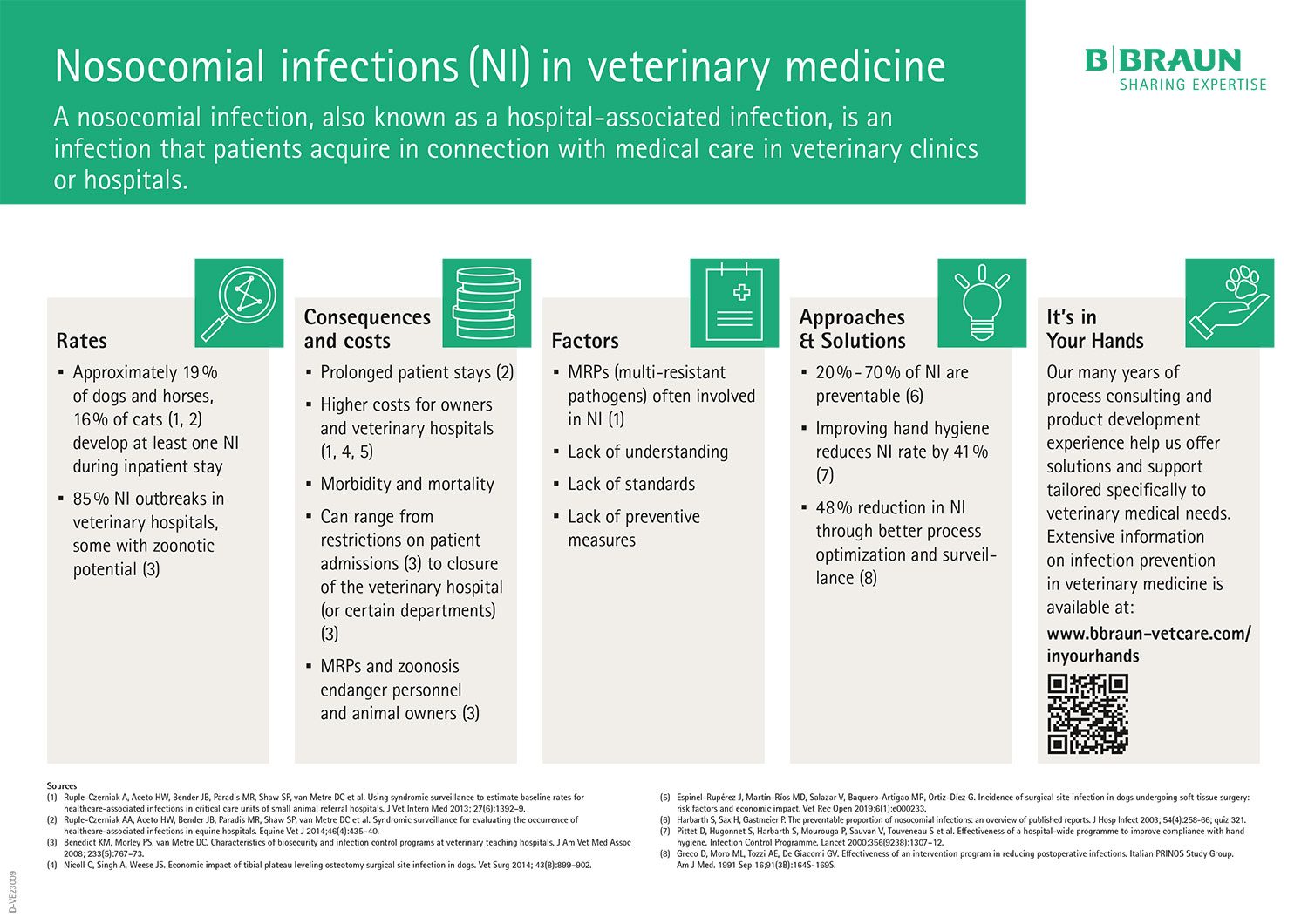

Nosocomial infections (NI) in veterinary medicine

A nosocomial infection, also known as a hospital-associated infection, is an infection that patients acquire in connection with medical care in veterinary clinics or hospitals.

The risk of developing nosocomial infections differs depending on any underlying diseases or the medical procedures being carried out.

In the veterinary field, there is little data on NI/HAI compared to human medicine. One study showed that 19 percent of dogs and horses and 16 percent of cats develop at least one NI/HAI during their hospital stay. Significant differences (8 to 36 percent) were found in the various clinics. [1, 2]

Several veterinary clinics witnessed at least one nosocomial outbreak in, [3, 4] while 45 percent of clinics even reported several outbreaks during the time period in question. Many of these outbreaks incurred a limit on the number of patients being admitted (58 percent) or caused veterinary clinics or individual departments to close (32 percent). [4]

NI/HAI consequences include prolonged inpatient stays, as well as additional and more frequent intensive treatments – usually entailing higher costs for patient owners and veterinary clinics and practices. NI may have long-lasting health consequences for patients and may even result in an animal’s death. [1]

Multidrug-resistant pathogens (MREs) are often involved in NI/HAI, making treatment especially difficult. In addition, some hospital-associated pathogens (e.g., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] can infect staff or animal owners resulting in illness. [5-8]

Due to rapid developments in veterinary medicine, especially in intensive care and surgery, NI/HAI is becoming increasingly important and has a considerable influence on a treatment’s success. In human medicine, it is assumed that 10 to 70 percent of all hospital-acquired infections can be prevented by simple and easy-to-implement infection prevention measures. [9]

The proportion of preventable infections in veterinary medicine is not known, but is likely to be similarly high or even higher, as comprehensive infection control is not yet standard in veterinary practice. This poses a risk to both animals and humans. Nosocomial outbreaks due to Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius [10] and feline calcivirus [3] are generally known.

Pathogens such as Salmonella spp. [4, 11] or S. aureus have also been associated with nosocomial outbreaks and pose a zoonotic risk to staff and patient owners. [4, 12]

A reduction in infection rates is therefore not only associated with better patient outcomes, lower costs, happier customers, and less stress (emotional and rational) for veterinary staff, it is also an important aspect of occupational health and safety. This is particularly because a reduction in NI/HAI can be achieved through simple basic and process hygiene measures. In 2002, when the CDC Guidelines for Hand Hygiene in Human Medicine were issued, hand hygiene compliance in human medicine was 40 percent (5 to 81 percent). In their work, Pittet and colleagues (2000) showed that an improvement in hand hygiene compliance from 48 to 66 percent was accompanied by a significant reduction in nosocomial infections (prevalence from 16.9 percent in 1994 to 9.9 percent in 1998; p=0.04), as well as a significant reduction in the transmission rate of multi-resistant S. aureus. [13]

[1] Ruple-Czerniak A, Aceto HW, Bender JB, Paradis MR, Shaw SP, van Metre DC et al. Using syndromic surveillance to estimate baseline rates for healthcare-associated infections in critical care units of small animal referral hospitals. J Vet Intern Med 2013; 27(6):1392-9.

[2] Ruple-Czerniak AA, Aceto HW, Bender JB, Paradis MR, Shaw SP, van Metre DC et al. Syndromic surveillance for evaluating the occurrence of healthcare-associated infections in equine hospitals. Equine Vet J 2014; 46(4):435-40.

[3] Reynolds BS, Poulet H, Pingret J-L, Jas D, Brunet S, Lemeter C et al. A nosocomial outbreak of feline calicivirus associated virulent systemic disease in France. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11(8):633-44.

[4] Benedict KM, Morley PS, van Metre DC. Characteristics of biosecurity and infection control programs at veterinary teaching hospitals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233(5):767-73.

[5] Bergström K, Nyman G, Widgren S, Johnston C, Grönlund-Andersson U, Ransjö U. Infection prevention and control interventions in the first outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in an equine hospital in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand 2012; 54(1):14.

[6] Cuny C, Witte W. MRSA in equine hospitals and its significance for infections in humans. Vet Microbiol 2017; 200:59-64.

[7] Tillotson K, Savage CJ, Salman MD, Gentry-Weeks CR, Rice D, Fedorka-Cray PJ et al. Outbreak of Salmonella infantis infection in a large animal veterinary teaching hospital. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997; 211(12):1554-7.

[8] Dallap Schaer BL, Aceto H, Rankin SC. Outbreak of salmonellosis caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Newport MDR-AmpC in a large animal veterinary teaching hospital. J Vet Intern Med 2010; 24(5):1138-46.

[9] Harbarth S, Sax H, Gastmeier P. The preventable proportion of nosocomial infections: an overview of published reports. J Hosp Infect 2003; 54(4):258-66; quiz 321.

[10] Grönthal T, Moodley A, Nykäsenoja S, Junnila J, Guardabassi L, Thomson K et al. Large outbreak caused by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius ST71 in a Finnish Veterinary Teaching Hospital – from outbreak control to outbreak prevention. PLoS One 2014; 9(10):e110084.

[11] Walther B, Tedin K, Lübke-Becker A. Multidrug-resistant opportunistic pathogens challenging veterinary infection control. Vet Microbiol 2017; 200:71-8.

[12] Stull JW, Brophy J, Weese JS. Reducing the risk of pet-associated zoonotic infections. CMAJ 2015; 187(10):736-43.

[13] Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, Mourouga P, Sauvan V, Touveneau S et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection Control Programme. Lancet 2000; 356(9238):1307-12.